Mon, 02/22/2016 - 12:09 by karyn

It kicked off with a scream for change and an antistyle. Punk rock as we know it grows its roots from counter culture protest. Bringing everything that is considered ugly or marginal straight in your face with nothing less than grand shock value, it comes off as raw, persuasive, radical, unconventional and without rules. Heath Cairns, Montreal-based graphic designer and longtime punk appreciator, was telling me earlier this year how "the first wave of American punk and hardcore in the early 80's was a reaction to Ronald Reagan taking power in 1980". Unless they gave up the core ideas of the movement, punkers had no place in mainstream culture – a sentiment shared by skateboarders. And so, perhaps inevitably, the two subcultures came together. For Vancouver-based graphic designer and illustrator Tim Barnard, "Skateboarding, music and arts, they're so intertwined". The draw? The possibility to define one's identity through freedom and creativity.

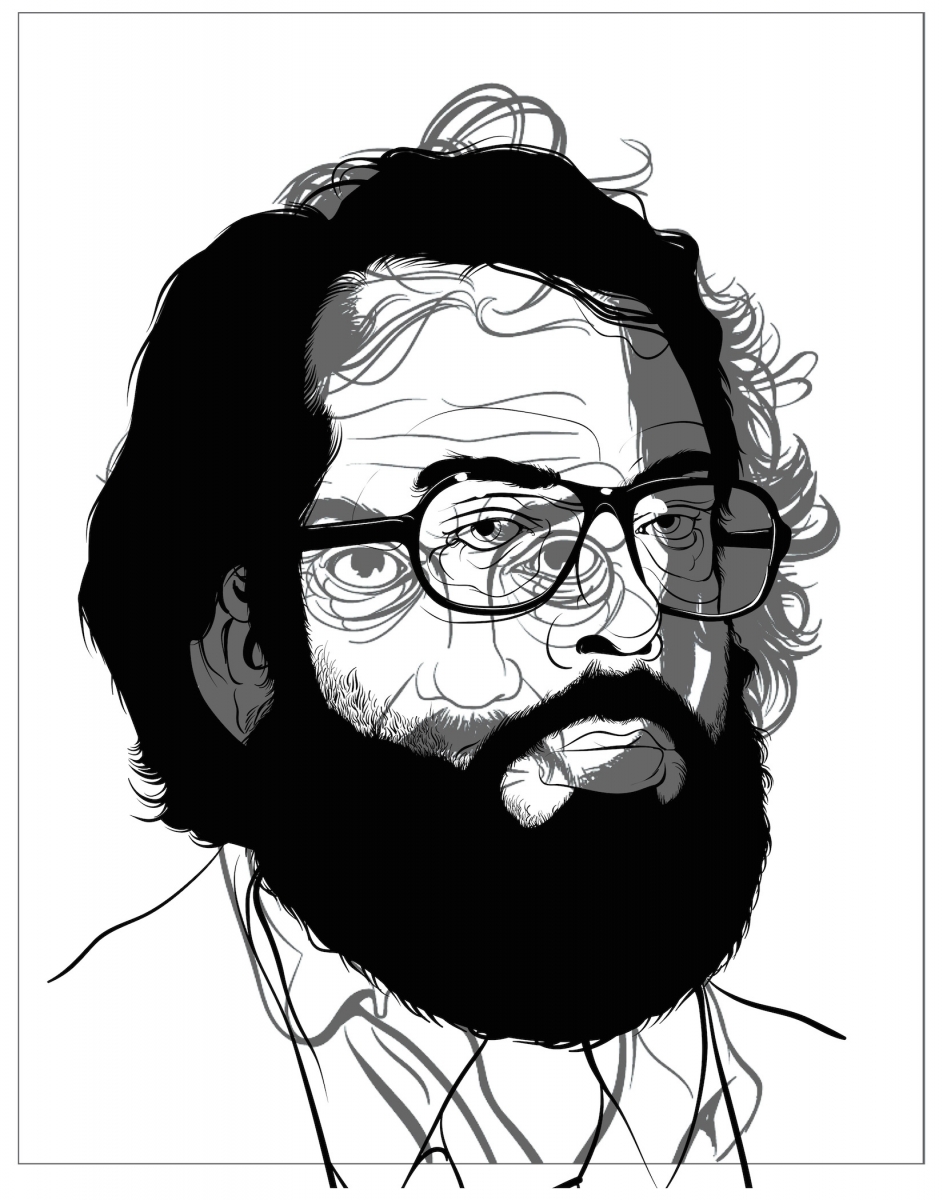

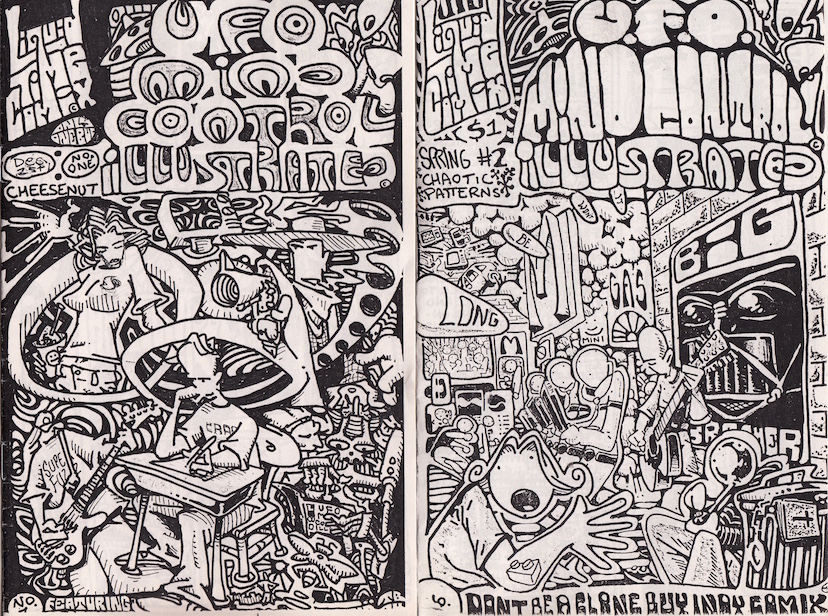

Both Montreal and Vancouver based artists mentioned above have lived through the 80's punk subculture and still see their work influenced by it. While nineteen-year-old Heath Cairns landed his first gig through a friend in a band called Uncommon Society —he was asked to do their 7-inch cover— young Tim Barnard flirted between tattoo and graphic design, photocopying his gig posters and making his own comics. He ultimately started working at a tattoo shop at fifteen. Punk rock has always had a unique and complex aesthetic with its own language and self-reflexivity. In the 80's, this was "kind of a big giant can opener for people's minds," claims Tim Barnard, who likes to see most his work as "some sort of reaction and deconstruction of [society's expectations]". Punk allowed people to "deprogram" themselves from the norms and stray from the beaten path. It allowed for analysis and interpretation of a society in hopes of enhancing cultural understanding.

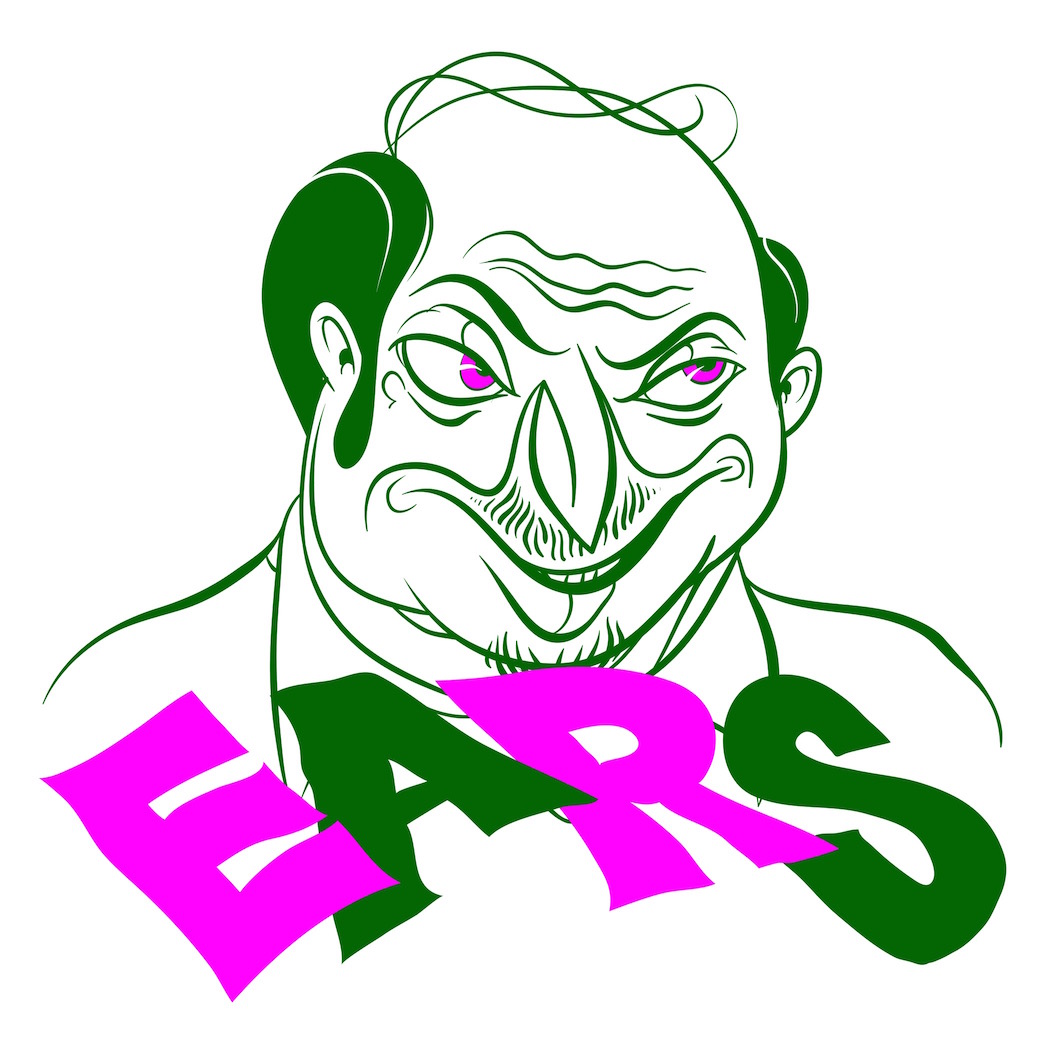

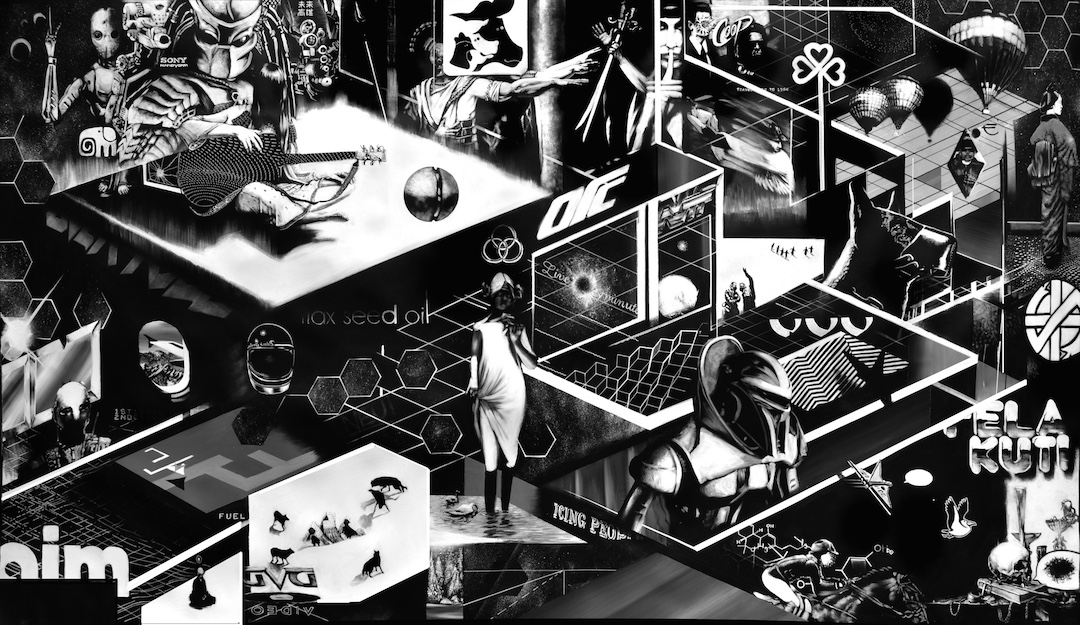

As for its aesthetic — the influence of which can be seen in Cairns and Barnard's work— it was composed of collage, cartoon drawings, hand-lettering, ransom-note lettering, stencils, black and white, offset litho, Xerox photocopying... anything that was different, really. “It [Punk's aesthetic] was steeped in shock value and revered what was considered ugly. The whole look of punk was designed to disturb and disrupt the happy complacency of wider society. Outside of punk's torn and safety pinned anti-fashion statements, this impulse to outrage was never more apparent than on punk album covers," once stated Los Angeles artist Mark Vallen. The Sex Pistols' album cover for Never Mind The Bullocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols —with its ripped up photocopy aesthetic of artist Jamie Reid— was a perfect example of this. "Jamie Reid was also the guy who put the safety pins through the Queen's nose. That kind of imagery was really loaded,” adds Cairns.

As well as rock music and art, skateboarding also appropriated features from its past and recontextualized things in order to negate their original capitalist aspect, fashioning different tastes, styles and images. But the imagery didn't only show itself to be strong on punk album covers or in skateboarding's graphics. Punk zines were loaded with haphazard layouts along with a nasty, funny, acidic and sarcastic wit. Moreover, Mark Perry's Sniffin' Glue was actually the publication that pioneered the DIY punk ethic. Today, the DIY ethic —probably the most praised punk ideology— promotes individual freedom through a direct action. The acronym DIY, "Do It Yourself," is self-explanatory: be the change you want to see, don't be afraid of being right on the edge of society's norms because nothing is standing in your way. Cairns and Barnard, regardless of their implication in projects that at first glance may not come off as punk rock —POP Montreal or The Royal Mint of Canada, for example— still have that hidden narrative in their work. They believe in doing things differently; and by differently, I mean out of pure joy and personal satisfaction. "To make a career out of illustration, you have to decide that's what you're going to do and keep at it until people notice. [...] It's easier now than it was then to be DIY," adds Cairns. "The best thing about punk rock is that the DIY ideology behind it is really empowering. You don't have to ask anybody for permission. You just do it."

In the end, there is always a punk rock element if you look for it. In Tim Barnard's art, you see it right away in the aesthetic: the black and white look, the comics of multi-faceted imagery, the clinical dissection of his work, the hard edge graphic media. In Heath Cairns' work, it's not only in the imagery, but also in the attitude. He still takes on many poster gigs and never approaches galleries, because he simply doesn’t care for it. "Maybe in all this digital stuff, the most punk rock thing is just for a kid to pick up a pencil and get enjoyment out of that," Tim Barnard points out. "As long as it's subtly different from what we're programmed to supposedly be doing." And he might be spot on. Maybe, in today's reality, the most punk rock thing for us to do is to step back from what we're used to and start carving out a life that feels truly authentic in the way we feel best about.

Add comment