Sat, 05/14/2011 - 00:00 by Douglas Haddow

What could the world possibly owe four hyper-educated, Ivy-League white males in their late 30’s? A readership, perhaps. At least that’s the case with Marco Roth, Benjamin Kunkel, Keith Gessen and Mark Greif, the founders and editors of n+1, the literary journal that’s positioning itself at the forefront of contemporary critical thought. Modeled on journals like T.S. Eliot’s Criterion, The Partisan Review, and Dissent, n+1 attempts to channel the critical fortitude of patron saints like Edmund Wilson, Lionel Trilling and Alfred Kazin.

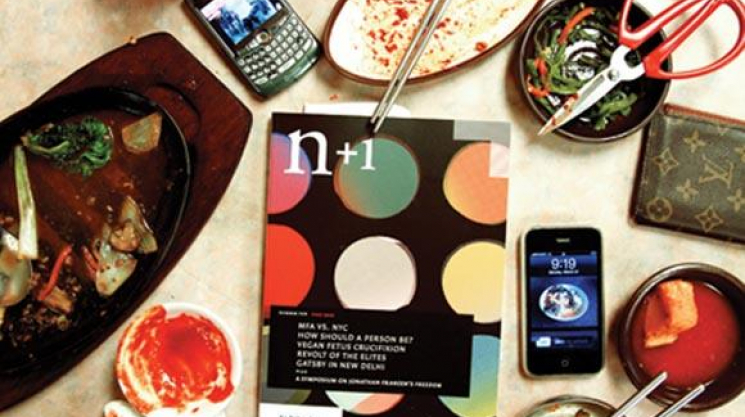

Noteworthy admirers like Jonathan Franzen and Mary Carr praise the magazine to such heights as to call it “the best goddamn literary magazine in America,” while detractors often allege intellectual-posturing, and mere sophistry. A 2006 article in The New Criterion once called n+1 the “must-have accessory of the self-styled smart set” and predicted a quick demise, but it’s been 5 years since and it’s long outlived that prediction and found a stability (both financially and in its convictions) that hints that n+1 is climbing in the first stages of a vast, upward trajectory.

Conversation with founder and co-editor, Mark Greif, is an intense experience; answering questions in whole, breathless paragraphs with erudition and care; treating both low and high-brow subjects with equal inquisitiveness. Greif wrote a lauded essay on Radiohead (“Radiohead and the Philosophy of Pop”) and during our conversation wondered aloud about the details of Canadian tax code — talking to him is, at least in inclination and wordcount, akin to reading the magazine itself.

To tell the story of the conception of n+1, Greif assesses the state of politics and literary criticism back in the year 2004. Politically, on the heels of Bush II and in the wake of Operation Iraqi Freedom, he had to look no further than the shallow dialogue of the public sphere. “You looked around at the time and there was this illusion, or at least people would say it out loud in the media, ‘We’re having a discussion about the coming war in Iraq’,” continuing, “you see people on TV and they’re saying, ‘We have orange here, and orange is disagreeing with red, but thank god we’ve got a lively debate going here with the whole spectrum of opinion and belief’ — incidentally it doesn’t really matter because the cruise missiles should be hitting right about now, and any sane person had to say to himself, this is a discussion? It was demented.”

For English scholars like the founders of n+1, where they once would hope to find intellectual solidarity — they were only met with further frustration. Greif and his friends saw problems coming from all angles, exemplified in certain publications. So in their first issue they drew out polemics against these magazines; The New Republic for being literary Luddites in their bitter and dismissive reviews, McSweeney’s and The Believer for being precious, sentimental, infantile and ultimately hocking a “regressive avant-garde,” and the conservative The Weekly Standard for outright lying. “We wrote up all these things that we thought should drive everybody crazy, and then we waited to see who would respond,” Greif says. This kind of provocation is natural in the journals insistence of the importance of argument and dialogue. In an interview with Brian Lehrer in 2006, Greif, in a defense of literary postmodernism said, “it’s very important to say we are great fans of postmodernism, of the youth culture, and of sexual liberation, and if anything, we should go too far — you know, we believe the sexual revolution should have been carried all the way and the family destroyed and civilization started on a new foundation.” It’s a semi-facetious comment, but it’s an example of how even digressive lines of thought are outsized in their affronts, and no doubt these guys possess the argumentative firepower to make it a convincing proposition. Greif explains a simple philosophy behind this gamesmanship, “literary culture, if it moves on, does so because people are arguing and learning from each other, and loving and hating what other people do, and you have to believe it comes to some higher synthesis.”

These agitations have seen results, soliciting responses from a range of public figures. James Wood, arguably the foremost literary critic in the world, came in defense of himself and The New Republic, issuing a letter n+1 printed in its pages. “That letter turned out to be a pretty great essay. Of course he was still wrong about everything, but, as I said, he’s for real, always was.” Just recently, as n+1 editors published a surfeit of essays on the sociology of the hipster in the New York Times and New York Magazine, Gavin McInnes tweeted his desire to punch the n+1 editors in the face. Ultimately it’s this sentiment, lobbed from the former Vice Magazine mensch nonetheless, that signals n+1’s ascendance into cultural primacy. That McInnes and his old institution’s ethics of provocation, steeped in frivolity, irony, thoughtlessness — the empty gestures of controversy and attention-seeking — are finally laid to rest in favor of n+1’s methods of academic rigor, creative enthusiasm, intellectual engagement, all in the unending pursuit of “The New”. As Greif puts it, “people always seemed to be finishing stuff up. This is dead, that is dead, this is done, etc. Not true. I’ve got an Emersonian streak — each time somebody’s born, they start the whole world from scratch. So the idea was just, in every art, and every endeavor, all we have to do is indicate that, you know, there’s another step. Nothing’s over.”

It’s probably worth it to note that James Wood made the pretty incisive observation that n+1 so far, has not itself established what exactly “The New” is, or should be. There’s plenty of time. With only 10 issues under their belt, the magazine can be considered just out of its infancy, although it still retains the attitude of the brash new kid. Just recently upping their production from two to three issues a year, and with a host of projects in the pipeline for their “n+1 Research Branch” small books series, n+1 is in great shape for the future. While other magazines atrophy in a narrowness of idea or aesthetic, n+1 takes on a more mercurial existence granted in the belief that the argument and the question are the most arduous forms of thought. And if they ever do lose their vivacity, their curiosity and passion? Greif answers, “We would need a younger magazine to kick our asses, right away.”

Add comment