Fri, 03/18/2011 - 00:00 by Douglas Haddow

“WHITE FRIGHT”

Some satirists gently prod society with a pointed finger. Others are more severe, slapping their subjects across the face with the backhand of ridicule and then gouging their eyes with scornful fingers.

Anton Kannemeyer, aka “Joe Dog”, invites his target to gently rest their head within the vice of familiarity, squeezing its jaws shut until everything hidden away spills inside out.

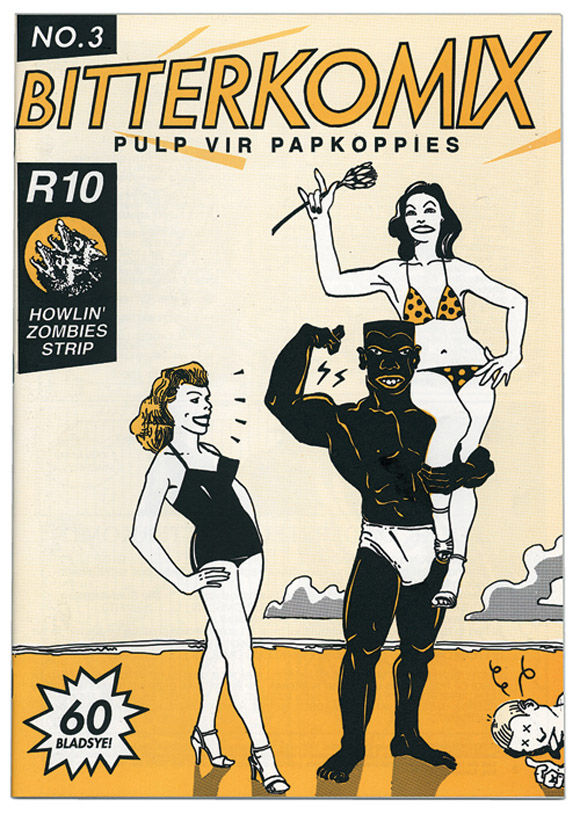

The results are often terrible, funny, and viciously comic. Kannemeyer developed his style while co-editor of Bitterkomix; a South African cult comic magazine that was founded in 1992 and has insulted and dismantled South African politics ever since.

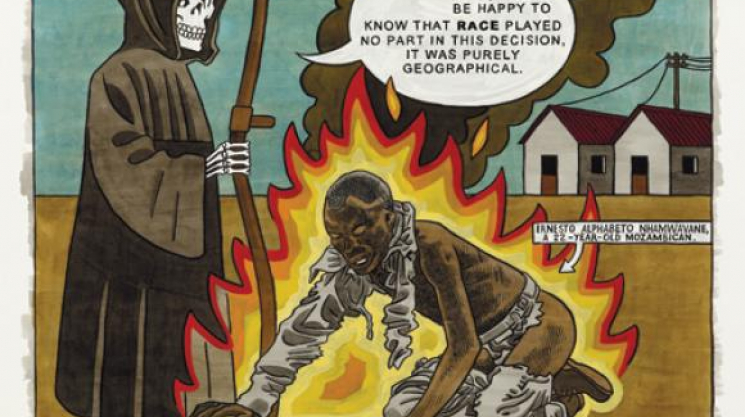

Kannemeyer built a reputation on his machete-sharp wit and aesthetic versatility. In 2010, he published a collection of work under the title Papa in Afrika in which he flawlessly imitated the style of Hergé and repositioned the beloved Tintin as a symbol of colonialist violence.

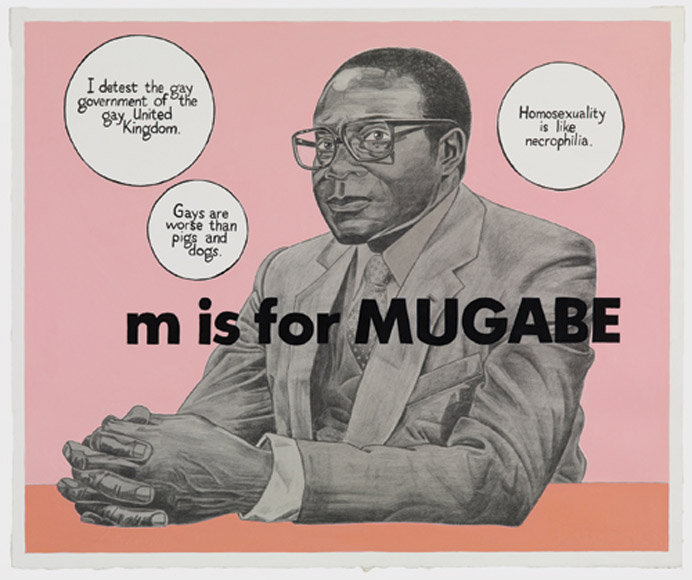

These days, Kannemeyer is collaborating with fellow Afrikaners Die Antwoord, and preparing for a solo gallery show at the Jack Shainman Gallery in New York City. He has a new book out, The Alphabet of Democracy – “an A to Z guide to the absurdities of life in the democratic South Africa.”

ION caught up with him recently from his laptop in Cape Town and talked about the state of pretty much everything.

What do you make of the recent spike in popularity of South African pop culture?

I’m not sure why South African pop culture has suddenly become quite a thing internationally. Firstly, I guess, it took a bit of time since the end of apartheid and cultural isolation to get standards on a par with what’s happening internationally. The one thing that Neil Blomkamp, Die Antwoord and myself have in common is Afrikaans, and the Afrikaners are an interesting bunch. On the one hand you have a large conservative group, on the other you have those (like us) who have rejected Afrikaner culture and traditions. I think the break with our culture is traumatic and severe, and therefore it’s normally an all-or-nothing kind of situation. To give you an anecdote (and I do this to explain, even though I don’t think you’ll understand it really, you’ll probably consider it an isolated incident, but it isn’t, there are many!):

I remember I had a drawing lecturer at university who was English – I really liked him; he was witty, articulate and very critical of Apartheid. I soon started to work on my Bitterkomix series and in 1994 we made a very explicit sex comic that looked at taboos and fears in Afrikaner culture. I remember he asked if he could buy a copy from me, then returned it the next day and NEVER spoke to me again. At that stage I was a part-time lecturer (doing my MA) and he just ignored me. What I realized was that I had overstepped a certain boundary with him, maybe something about decency or a moral standard that he couldn’t accept. This I found to be quite typical in South Africa: white English speakers generally came from a liberal background, which always kept them more or less in that position – there was a lot to reject and fight, but not as much as Afrikaners had to reject and fight.

I think once Afrikaners start rejecting, they’ll go all the way. There are quite a few examples, like Breyten Breytenbach, who was a poet, but eventually he tried to plant a bomb. Anyway, this does not explain why South African pop culture has become interesting…

I think I get what you’re saying, that this break with the culture allows Afrikaners to get an entirely new perspective. Which also speaks to your work – how it can engage on a purely visual level, but also belongs to a specific South African political context that most people aren’t familiar with. if there is one thing the average Canuck should know about South African politics, what is it?

Generally speaking, I think the South African political scene is quite a complex one. We have 11 official languages, and that should be an indication of the complexity of the political situation. Before the fall of Apartheid only white people had the right to vote. These white people were (and still are) divided into two linguistic/cultural groups: Afrikaans and English. It’s common knowledge that the Afrikaners had the political power since 1949 and the English had the economic power since, well, since the Anglo Boer war in 1899. Needless to say, the white English speakers benefited handsomely from Apartheid, even though most of them always claimed to be “liberal” and critical of Apartheid.

Since 1994 (the first democratic elections in SA) the ANC has been the dominant party, consisting mostly of Xhosa-speakers, like Nelson Mandela, and Zulu speakers, such as our current president Jacob Zuma. The various ethnic groups are of course spread across the country, but the Xhosas are originally from the Eastern Cape, and the Zulus from KwaZulu Natal. Cape Town, where I live, has a large group of coloured (mixed-race) people. To give you an idea of numbers, I would say that the white population consists of about 10% of all South Africans, the coloured population about 5% and more than 80% of all South Africans are black. There is also a substantial Indian population, and then various other minority groups.

One of the most arresting aspects of your work is how you approach horrendously complicated topics with a simple, satirical comic style. What do you like about working in the comic aesthetic?

I think that a comic style allows one to easily access stereotypes, which is important if you’re a satirist. The simpler the image becomes, the clearer it is for the viewer to read the image. The problem, however, is that the image may look simple, but the message is often complex. It so happens that a lot of people, especially visual illiterates, may think they understand the image because it’s drawn in an accessible comic style, but the meaning may be ambiguous or hidden. This often leads to misinterpretations and controversy. In Alphabet I have used the black stereotype, or “blackface,” less often than in Pappa in Afrika, so you’ll find more “realism” in the Alphabet series. But it still uses a lot of comic devices. Another reason would simply be that I come from a comic background – I used to draw comics primarily.

And in some instances you’ll have a “blackface” character and a more realistic character occupying the same frame, as in “This is how it works.” What is the significance of this contrast?

Personally I don’t think this is one of my stronger works. It’s probably interpreted as if I’m siding with the “round” character (the realistic guy) and I’m saying that the stereotype is the bad one ripping the “worker” off – and therefore he deserves to look like a stereotype. This was a bit obvious, and although I am personally outraged by the greediness of many politicians across Africa, I do not want to be a moral crusader on behalf of the poor. I believe this to be dishonest, and as a satirist it’s problematic to jump on a moral high horse – as if I’m not complicit at all (and here I’m not talking about racism, I’m talking about a deep-seated sense of guilt and of course the fact that I’m white – so I cannot appropriate the position of the black worker.) I think this is very important in my work, to show my complicity, to check and recheck my own fears and prejudices.

What sort of reactions have you received from the South African political establishment, if any?

I don’t think my work has had much impact on the political establishment. Unlike Zapiro, our most famous political and editorial cartoonist, my work is primarily seen in art galleries and not in newspapers. Therefore I’m probably preaching to the converted, although I do get a lot of flak from white liberals, and occasionally black liberals.

I think you would provoke a fair amount of Canadian liberals as well, as talk of race or racial politics is a rare occurrence in Canada, the prevailing self-image being one of multicultural harmony. if a Canadian were to produce a similar style of dark, challenging racial satire, the artist would probably be brought in front a human rights tribunal for disrupting the peace, which begs the question – is it necessary to create art capable of provoking discomfort?

I think this has to do with the way I approach my work. I feel strongly that my perspective should be as unique as possible, and maybe therefore I also don’t always address the most obvious situations or incidents. I’m programmed to make work that makes people uncomfortable; to a large extent that’s the aim. I want people to think about my work. I’ll never be satisfied with a mediocre response. I want them to be angry and hate it, or feel the opposite and love it. Personally, I feel the Alphabet series to be a bit more moderate, and at the moment it looks like it’s doing very well in South Africa, meaning, the reviews and sales are all very positive. Which is rather weird for me – I’m moving into the mainstream it seems… The racial harmony in Canada sounds a bit unreal… My experience is that racism is everywhere. But I have never been to Canada, so I can’t tell!

Following that up, there seem to be two primary reactions to your work – either that it’s a subversive critique of bigotry and political correctness, or, that it’s cynical and racist. Both readings boil down to where you, personally, sit on the spectrum of “progressive” politics. But it feels like these two readings are inseparable when it comes to the subject matter. My question being, is it necessary to indulge racism in order to examine it?

Firstly, I think the work should read as an investigation of race and a critique of racism. It’s satire. Also, I think in terms of a body of work, isolated parts could be misinterpreted as being racist. I can understand that, but it’s like taking one panel from a comic and criticizing it independently – which is wrong. I mean, you wouldn’t take a paragraph from a novel and then try to prove the writer is a racist on that basis – you would read the novel as a whole. Pappa in Afrika has many jarring juxtapositions, jumping from realist imagery to very iconic imagery – and that’s very deliberate. And it should be read as a whole. My political position should be irrelevant and the work should stand on its own, reading as a body of work that attacks white people and white interference in Africa firstly. If it doesn’t, I have failed as an artist. If it only depends on me saying afterwards “hey, I’m actually anti-racist,” it’s not enough.

The main problem with my approach is that I’m not following current PC-protocol, and that’s why white liberals are angry with me. Regarding the actual question: I have made a lot of work looking closely at race, and I found that reducing the image(s) to stereotypes deals most directly with the problems I’m addressing. The one thing I tried to do in Pappa was to create a white stereotype as well. It’s a black vs. white or white vs. black realm that I deal with and stereotypes are the most effective. It’s also common knowledge that stereotypes form part of the satirist’s armoury. I am aware, and this is of course very ironic, that I’m “indulging” racism as I’m examining it. I don’t think this is a necessity, but it certainly helped to clarify a particular body of work.

You mention how you deliberately jump between realist imagery and iconic imagery – this is interesting as I find some of your work to have a very journalistic feel to it. For example, the Cursed Paradise series, various pieces from Alphabet of Democracy in which you frame politicians next to statements they’ve made, and works like Boy Soldiers in which you quote journalists verbatim. Would you say that there is a documentary component to your more realistic work?

Certainly! I remember when I first saw Fernando Bryce’s work and I thought “Wow! It’s amazing that someone can do this!” I think the problem with recent African history is that there are not enough books out there. I was looking in Strand in New York for historical books on 20th century Africa and there was maybe a single, half-empty shelf reserved for all of African history. There were shelves and shelves of books on the Holocaust in the same sectionn They even piled them up in the corridors to accommodate them all.

A visual history of 20th century Africa is even less available. You have several on tourism in Africa, beautiful books on animals and so forth, but nothing with a visual history. “Why is this?” I thought. Is no one interested? Are white people too ashamed of the legacy of slavery and the plundering of Africa? So in a sense I thought that the documentary aspect is crucial, although it’s very fragmented and selective.

So is Alphabet of Democracy intended to serve as something of a historical text?

I started the Alphabet series when I read several pieces on Bitterkomix in the media commenting on the fact that Bitterkomix gives a good account of the transition between Apartheid South Africa and the new South Africa. I thought that I’d make an extended work dealing with this change of power. The selection of images and ideas are all very random from my scrapbooks, focusing mainly on things that I find interesting. So in a sense it’s a bit of a personal account, and if it becomes of any historical significance I’ll be delighted.

Add comment